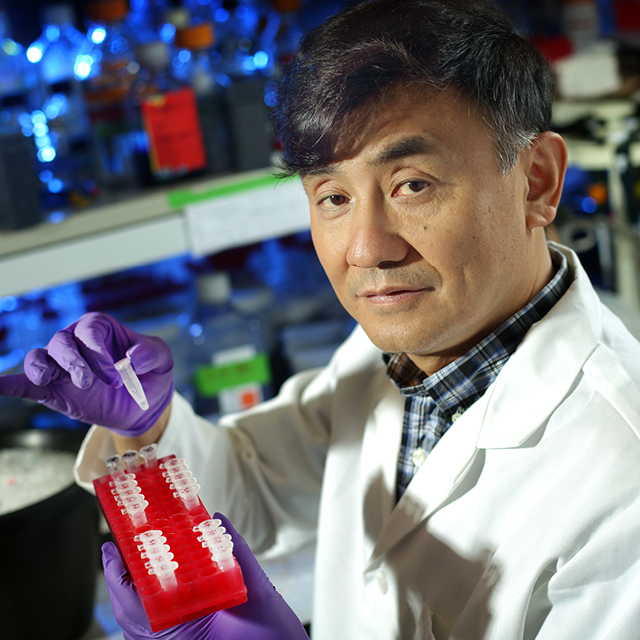

Although there are currently no treatments that can modify or halt the course of osteoarthritis in its trajectory, research led by Xu Cao, professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, may change that.

About five years ago, Cao’s team unveiled a new hypothesis about the biology of osteoarthritis and how it first unfolds. Unlike other prevailing views of the disease, which focus primarily on the articular cartilage, Cao’s research centered on articular cartilage and subchondral bone as a functional unit, particularly the molecular signals that drive the pathological changes of the subchondral bone on cartilage. The team showed that by intercepting the signals of the protein called TGF-ß1, they could stave off the development of osteoarthritis in mouse models of the disease.

Cao and colleagues, both at Johns Hopkins and at research organizations in China, are now working to translate this discovery into novel therapies for osteoarthritis patients. They are studying two different types of TGF-ß1 inhibitors: One is a small molecule inhibitor linked to the osteoporosis drug bisphosphonate, and the other is a chemical analog of a plant-derived compound used in ancient Chinese herbal medicine to treat malaria. The latter inhibitor, known as halofuginone, is now undergoing clinical trial in China to evaluate its safety and efficacy.

Share Fast Facts

Groundbreaking research by orthopaedic surgeon Xu Cao & his team may lead to novel disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis. #arthritis Click to Tweet

The trial, which opened in June, seeks to enroll 40 patients with early stage osteoarthritis of the knee. Participants will receive a single injection of halofuginone into the subchondral bone under the guidance of an orthopaedic surgeon. This clinical approach is unique among groups currently evaluating potential therapies for osteoarthritis, says Cao. Other investigators typically inject therapeutics into the synovial cavity surrounding the joint. Halofuginone is directly delivered into subchondral bone to inhibit excessively active TGF-ß1 and a progression of osteoarthritis.

Participants in Cao’s trial of halofuginone will be followed for one year and monitored both for improvement in joint pain as well as reduction in bone marrow edema in the subchondral bone as visualized by MRI. If successful, the trial in China could enable future trials in the U.S.

“There is no disease-modifying therapy for osteoarthritis, period. So if halofuginone proves safe and effective, it will be the first of its kind,” says Cao. “More broadly, it will also represent a real change in philosophy for how skeletal diseases are treated—addressing both mechanical loading and modulating molecular signals.”