Each year, doctors prescribe antihypertensive drugs to tens of thousands of Americans, with a large array of options available. These include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or ACEIs, and angiotensin II receptor blockers, or ARBs.

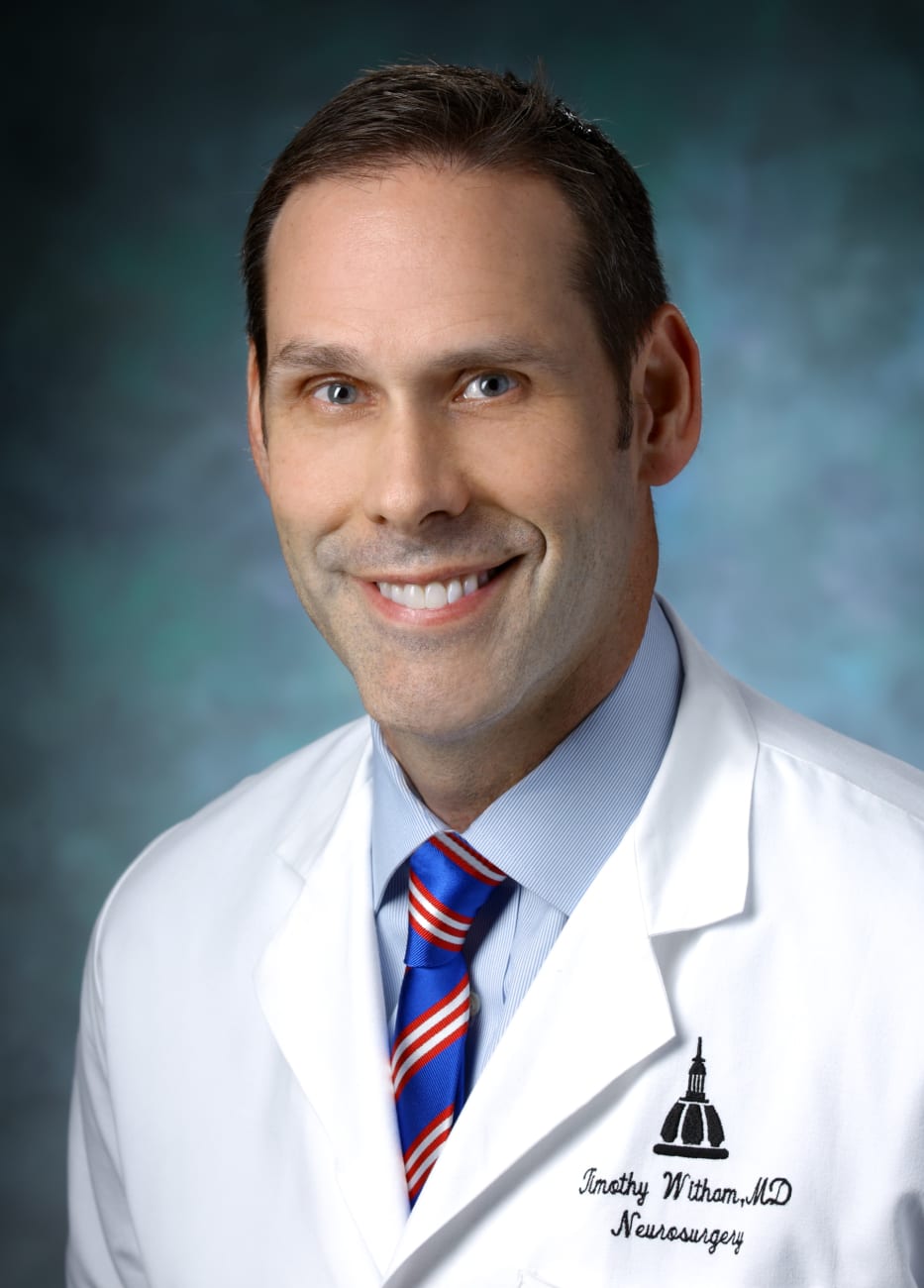

Prior evidence in the literature suggests that these drugs can have wide-ranging effects throughout the body, including on the function of bone-building osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts. But new research led by Johns Hopkins neurosurgeon Timothy Witham and published in The Spine Journal in August of this year, suggests that they can either slow or promote rates of spinal fusion clinically.

After Witham’s postdoctoral fellow Alexander Perdomo-Pantoja read about these drugs’ conflicting consequences on the cells pivotal for bone remodeling — with ARBs promoting the activity of osteoblasts and inhibiting osteoclasts, and the opposite true for ACEIs — they and their colleagues decided to review the records of 200 patients who underwent anterior cervical discectomy and fusion at Johns Hopkins. Of these patients, who had average age of about 54, about 39% were taking an antihypertensive drug: of them, about a third were on ACEIs, another third were on ARBs, and a final third took different types of blood pressure-lowering medications.

After each of these patients underwent their procedures, their surgeons tracked recovery rates within the bone itself using plain cervical X-rays and other imaging techniques if necessary. Their findings showed a stunning difference between the ACEI and ARB groups: those taking ARB drugs had fusion rates about twice as fast as those taking ACEIs. Those not on antihypertensive drugs had spinal fusion rates between these two extremes, suggesting that the drugs themselves were either helping or harming the fusion process.

Witham points out that, like most initial findings, more studies will be necessary to confirm these results in larger populations and with more diverse groups of patients, such as those undergoing similar procedures in other areas of the spine. His team is already working on the next phase of this research in lumbar fusion patients.

However, if the findings continue to hold true, they could have broad consequences both within his and other specialties. For example, he says, doctors may eventually take a patient’s blood pressure medication into consideration before performing spinal fusion as well as other types of orthopaedic bone surgeries. It could be advantageous to switch a patient on ACEIs to ARBs to encourage bone healing. Someday, he suggests, doctors could even prescribe ARBs to patients who aren’t currently taking an antihypertensive drug purely for a boost in healing rates.

“Tens of thousands of patients in the U.S. are on these medications that we’ve had no idea affected bone healing,” Witham says. “Our research is showing that we should pay attention to these off-target effects that could make a real difference in recovery from spinal fusion procedures.”

Timothy Witham’s lab is supported by a leadership gift from the Gordon and Marilyn Macklin Foundation and Jay Scaramucci.

TO REFER A PATIENT, CALL 410-955-7337.