Doorways to Discovery

November 11, 2014

Krakauer starts with the premise that we need to expand our thinking about the physical rehabilitation potential for stroke survivors. He notes that when a rodent who has had a stroke is placed in a setting with wheels, toys and “colleagues”—as Krakauer calls the animals’ cage mates—the recovery of its brain function is remarkable compared to humans’, whose rehabilitation routine has traditionally been governed by patterned limb movement.

Rehabilitation for stroke patients should include exciting visual, cognitive and motor activities, says Krakauer, who wants to capitalize on plasticity of the human brain to help patients maximize their abilities.

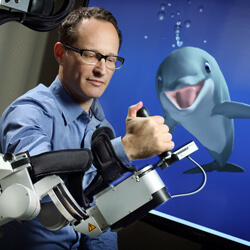

“The general belief is that the window of opportunity for significant and positive improvement in patients with stroke is about three months,” notes Krakauer. He and his Johns Hopkins team have borrowed from gaming, animation, animal behavior, robotics, philosophy, engineering and more to develop a new model for maximizing recovery within that time frame and perhaps beyond. The centerpiece of the model is a simulated dolphin—named Bandit and developed in the Brain, Learning, Animation, and Movement (BLAM) Lab—for new stroke patients to manipulate while it swims, jumps and hunts in the ocean. Krakauer’s collaborators, Omar Ahmad, Promit Roy and Kat McNally, designed the dolphin and the technology’s sophisticated gaming features based on long hours of studying the sea mammals at the National Aquarium in Baltimore.

The idea is to have patients control the complex acrobatics of the dolphin through flicks of their fingers, wrists and arms in a video game fashion, all the while sending streams of data back to the BLAM Lab. “It is a motivating, immersive and beautiful game,” Krakauer says.

In addition to its potential for therapy, the game, called I Am Dolphin, can be used for studies of normal learning. By analyzing data from hundreds of users, the scientists will also be able to see how increased skill in the control of this avatar changes over the hours that users play the game. The researchers will gain a wealth of information that would be nearly impossible to gather in a lab setting.

Krakauer’s team is about to launch a clinical trial involving recent stroke patients. His hope? That patients will get “lost” in being Bandit, playing as if they are frolicking dolphins. If they recover faster than patients who won’t be meeting this virtual dolphin, it could eventually shift the model for rehabilitation for patients with stroke and other neurological injuries and diseases.

Challenge: To design a way to improve functional capacity in stroke patients.

Approach: A team will track outcomes as recent stroke patients play a specially designed video game starring Bandit the dolphin.

Progress: Clinical trials of the video game are beginning.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital has been designated as a Comprehensive Stroke Center by the Joint Commission and Maryland’s Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems, a distinction awarded based on the capacity to offer specialized care to the most complex stroke patients on a 24/7 basis.