Dome 2019

March 26, 2019

Nina Martinez has lived with human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, since she was 6 weeks old. Now 35, she tries to fight misconceptions that still cause harm to people with the virus.

Giving a kidney to someone who needed it was the most meaningful way she could imagine to advance the cause, she says.

In most ways, the historic transplant was medically unexceptional. Its power came from its ability to help sweep away stigmas and barriers, paving the way for life-saving kidney transplants from people with HIV to others with HIV.

“There’s the perception that people like me, we bring death,” says Martinez, who lives in Atlanta. “But in this moment, I get to bring life.”

Early on March 25, Johns Hopkins surgeon Dorry Segev removed one of Martinez’s kidneys. Later that day, surgeon Niraj Desai transplanted it into a person also living with HIV.

Martinez and the anonymous recipient are doing well. They will continue taking the daily medications that ensure their HIV remains latent.

The donor’s brave act was just the latest development in long-standing campaigns by both Martinez and Segev to improve the lives of people with HIV.

“This is a celebration of the evolution of HIV care,” says Segev. “Today it’s not even a disease. It’s a condition. And for people with HIV, one of the biggest stigmas has been that they have not been able to donate a kidney.”

That changed in November 2013 with the signing of the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act, a federal law that Segev championed. It reversed a 1988 law forbidding the transplant of organs from people with HIV.

Martinez, 30 at the time, watched for developments in HOPE research. “I was hooked on the idea that I could become a living kidney donor,” she wrote in a January 2019 first-person account in Positively Aware. A few years later, she would be the nation's first.

Nina’s Story

“I think my whole life story and experience has prepared me for this moment,” Martinez says.

She and her twin sister were born 12 weeks early and required blood transfusions to treat their anemia. Martinez acquired HIV, though her sister did not. It was 1983, just two years after the first reports of an illness later known as AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Fear and confusion were rampant at the time. When 13-year-old Ryan White was diagnosed with AIDS the same year, his middle school tried to keep him out. It wasn’t yet known that HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, can be transmitted only through direct contact with bodily fluids. (People with HIV aren’t allowed to donate blood.)

Ryan died in 1990, when he was 18. In November 1991, Martinez remembers, she turned on her television and watched basketball superstar Magic Johnson announce he was HIV-positive. Martinez didn’t learn she had HIV until 1992, when she was 8.

She grew up believing she must be related to Johnson, because she didn’t know anyone else living with HIV. She felt different from everyone in her family, even her twin.

Her parents did not discuss her health status much, Martinez says, beyond telling her she was lucky to be alive. She didn’t expect to finish high school, much less graduate from Georgetown University and attend the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Martinez takes a daily pill to keep her virus at undetectable levels. She says she’s never experienced illness from HIV or side effects from the medication. But the virus, and the misconceptions around it, shape her life.

“People think someone with HIV has to look sick,” she says. “They also think people with HIV deserve it. To them, I’m a better person than someone who acquired it behaviorally.”

Martinez now works to reduce stigma and change laws that discriminate, such as a Georgia statute that makes it a felony to have consensual sex without disclosing HIV status.

In March 2016, she learned that Johns Hopkins had performed the nation’s first HIV-to-HIV kidney and liver transplants from a deceased donor.

Because of health concerns for potential donors, it would take three more years and additional research before the first live HIV-positive kidney donation. “We don’t want an HIV-positive donor to donate a kidney and then lose the function of the remaining one,” explains Segev.

A Hopkins research team, led by infectious disease specialist Christine Durand and Segev, determined that people with HIV have elevated kidney disease risk only when combined with other factors, including high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity.

“The real advance was our ability to really understand what the risks are, rather than saying that everyone with HIV is at risk for kidney disease,” says Segev. “Someone who does not have those risk factors, and has latent HIV, is basically just as safe to donate as someone without HIV.”

Martinez was an ideal candidate. Her kidney function is excellent, her HIV levels have always been low, and she is healthy and strong. She’s planning to run the Marine Corps Marathon in October.

Her public health background and HIV-related advocacy are added benefits, says Segev, noting that Martinez will contribute to the scientific studies that result from her kidney donation.

“When you do something innovative and exploratory, the innovators are not just the doctors. The real innovator — the real hero — is Nina.”

A Donation That Opens Doors

Last summer, Martinez learned through social media that a friend with HIV needed a kidney donation. She thought it could be her opportunity to become a living donor.

With an online search, she found a Johns Hopkins article about HIV-positive living donor transplants. In July, she sent an email to Segev, who invited her for evaluations.

Martinez traveled to Baltimore twice in October 2018 for days of tests, including a kidney biopsy. Then, the day after Thanksgiving, her friend died. In her grief, she thought carefully about her plan to donate. Martinez decided to go forward with the transplant anyway, and give her kidney to a stranger.

Multidisciplinary medical teams performed extensive medical evaluation in order to clear Martinez for donation, says Fawaz Al Ammary, medical director of the live kidney donor program at Johns Hopkins. Today, the Johns Hopkins team continues to carefully monitor her health to make sure her remaining kidney compensates appropriately for the lost one, says Al Ammary.

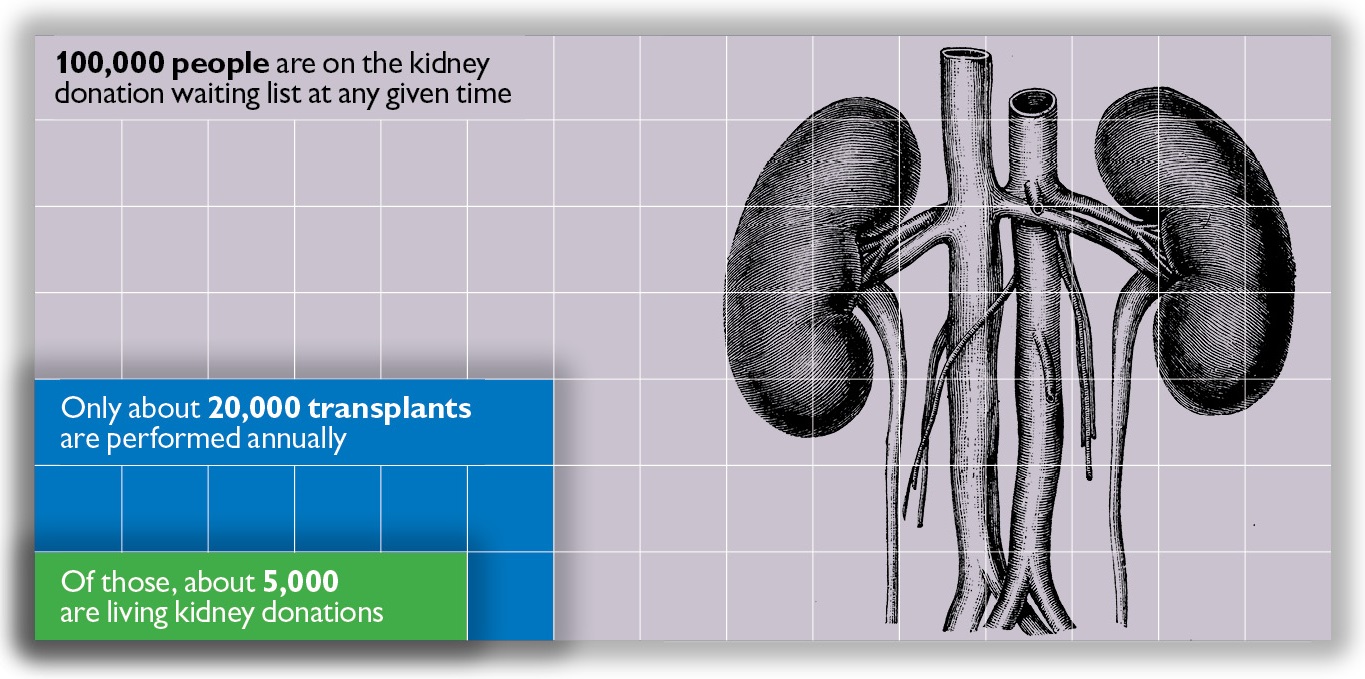

THE NATIONAL SUPPLY OF KIDNEYS FOR TRANSPLANT IS WOEFULLY INADEQUATE FOR DEMAND

“Kidney disease is rampant, and kidney transplants are probably the best form of treatment,” says Daniel Brennan, nephrologist and medical director of the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center.

The national supply of kidneys for transplant is woefully inadequate for demand. Although roughly 100,000 people are on the kidney donation waiting list at any given time, only about 20,000 transplants are performed annually, Brennan says. Of those, about 5,000 are living kidney donations.

The availability of kidneys from people with HIV opens possibilities. Because only people with HIV can receive kidneys from people with the virus, such transplants mean that recipients can skip the long waiting list, allowing those without HIV to move up a slot.

In the three years since the first HIV positive transplants from deceased donors, nearly 100 such transplants have taken place. The pace is accelerating, says Durand, as more people learn they are possible.

“If enough people knew they could give or receive HIV-positive kidneys, there would never be anyone with HIV on a transplant waiting list,” says Segev. “We have the potential for that. It’s a matter of getting the word to them.”

Martinez is eager to be part of that process. “What better way to refute the stereotypes?” she asks. “I was supposed to be the sick one. Maybe people will reconsider what they thought was healthy.”

Changing What's Possible

Dorry Segev, a professor of surgery at the school of medicine, uses mathematical models, legislation and advocacy to expand organ transplant opportunities. Read more in Hopkins Medicine.

For a timeline of HIV and AIDS advances: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/publications/hiv-aids-timeline/timeline.html

Correction: The information in this story was updated April 11. 2019 to reflect a correction to previously reported information. On March 25, 2019, Johns Hopkins Medicine performed the first living donor HIV-to-HIV kidney transplant in the United States. It was previously reported as the first in the world.”

Published in Dome March/April 2019